Are practical jokes still played on school leavers starting work these days?

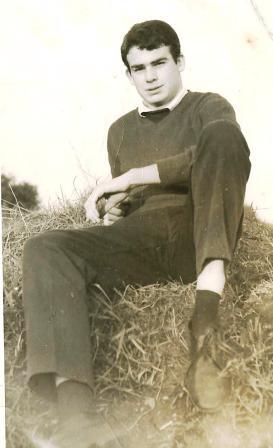

In 1963 I left school, aged 16, and started my first job in Oxford Street, London.

In 1963 I left school, aged 16, and started my first job in Oxford Street, London.

I had tried without success to find work as a trainee photographer, visiting studios all over London, showing my snaps to hard-grained photographers who laughed me and them away. So the local Youth Employment Officer, in desperation, suggested I start as a junior sales trainee in a photography shop. In equal desperation, with my parents nagging me to get work, I took the job at £6 ($10) a week.

Oxford Street, in the early 1960s, was a great place for a teenager to work and the shop was in the heart of the mod scene. I travelled in each morning on the tube from East London, where my family were living at that time. The hours were long, and I worked a five and a half day week, which included a late evening until 8.00pm on a Thursday. But the salesmen were a friendly, anarchistic bunch, no doubt taking their cue from Mr Rainbird, the manager.

Rainbird, as everyone called him, ran an easy ship, which included a fondness for playing practical jokes on his staff – and I was particularly green fruit.

On my second day in the job, he sent me on an urgent errand to buy a pound of earthing sand, ‘to spread on the cellar floor to reduce the risk of electrical shocks’. One of the salesmen, I was told, had suffered a nasty jolt down there ‘during a thunderstorm’.

My very basic secondary school education hadn’t included much science, and I was daft enough to believe such a magical compound existed. Anxious to please and impress my colleagues, I trudged the West End of London, meeting amused shakes of the head at hardware shops, until finally I was put out of my misery: ‘someone’s pulling your leg, son.’ I returned to the shop to be greeted with howls of laughter.

On another occasion Rainbird gave me a phone number. ‘One of your customers, Mr Waxman, wants to talk to you. He sounds upset and insists on talking to you.’ Wondering what I had done wrong to upset Mr Waxman, I phoned the number given to be told I was through to Madame Tassauds!

But the last straw was when The Beatles were due to appear on ‘Sunday Night at the London Palladium’. Rainbird, knowing my enthusiasm for the Fab Four, told me I could request free tickets from the theatre. The Palladium (a London theatre) liked to have a full house for the live broadcast, he told me. By this time I was suspicious of anything he said, but thought I had heard this before elsewhere – or wanted to believe it. So in great excitement, and encouraged by the other salesmen, I phoned from Rainbird’s office.

‘Is that the Palladium?’

‘Yes, dear,’ came the rather high-pitched voice.

‘Is it true there are free tickets for The Beatles’ show?

‘Yes, there are still some left. How many would you like?’

‘One, please.’

‘We are sending them out six at a time, dear.’

‘Really! But I only need one.’

‘Well, you can throw the rest away.’

Suddenly the penny dropped. Rainbird had intercepted my outgoing call on the downstairs line.

‘Rainbird. You bastard!’

He was in hysterics, but I could have taken a shovel and beaten his brains out.

I never did get to see the Beatles at the Palladium, and I parted company with Rainbird soon after.