John T Betsch & Bessie Coleman

John T Betsch’s grandfather was the first black millionaire in Florida. John himself was, in his daughter’s words ‘a race man’ who promoted the black community in the area.

John T Betsch’s grandfather was the first black millionaire in Florida. John himself was, in his daughter’s words ‘a race man’ who promoted the black community in the area.

In 1930 he, as a member of the Negro Welfare League, sponsored and promoted aviator Bessie Coleman who went to Jacksonville to appear in an air show. You can read about Bessie Coleman here.

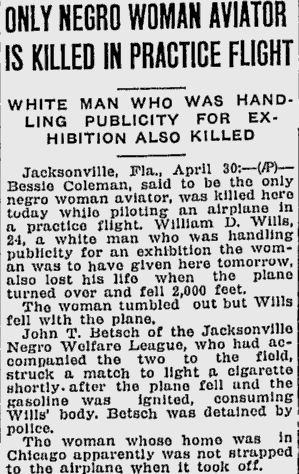

If you’ve read the article, you’ll know that the airplane became uncontrollable and both Bessie and her co-pilot were killed.

Bessie going to Jacksonville had been seen as a major event. Because she was the world’s first black licensed pilot and the world’s only black woman to hold a flying license.

Her forthcoming flying exhibition in Jacksonville was seen as being a triumph for her race. For days before she arrived in the town, celebrations were held in anticipation. There were parades, speeches, athletic events and church rallies in the local black community.

However, the exhibition was not to be as the fatal accident happened during a practise session the day before.

Sixty years later, author Russ Rymer was in American Beach, the black oceanside resort developed in the Jim Crow days. He mentioned the Coleman disaster to a local pilot and was met with a stony silence. He realised why when he was looking at old newspaper clippings about the accident and realised that there was an unspoken story.

Bessie had been thrown from the plane and plunged to her death. The co-pilot couldn’t correct the aircraft and it too plunged to the ground. When officials rushed to the scene to try to extricate the pilot, an official lit a cigarette. This ignited gas fumes and the wreckage and caused it to burn and explode – with the pilot still inside.

The man who lit the cigarette was John T. Betsch.

He had worked tirelessly to bring Bessie Coleman to the airshow in Jacksonville. He had arranged all the publicity for the event. And he ended up spending several hours – weeping inconsolably – in the Jacksonville jail during which time the accident was investigated.

His humiliation and despair were compounded further when he was described in the local newspapers as ‘John T. Betsch, negro. As Rymer says in the book you see below:

His attempt to showcase for his city the achievement of a race pioneer had made the papers as yet another demonstration of Negro mishap and shame.

Note: The book describes how rescuers found a telegram amongst the effects of William Wills, the co-pilot, that had been sent to him announcing the birth of a daughter he would never see.

There was also a book. In the flyleaf he had written:

Experience is what you get when you are looking for something else.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR