The Guinea Pig Club of the Second World War.

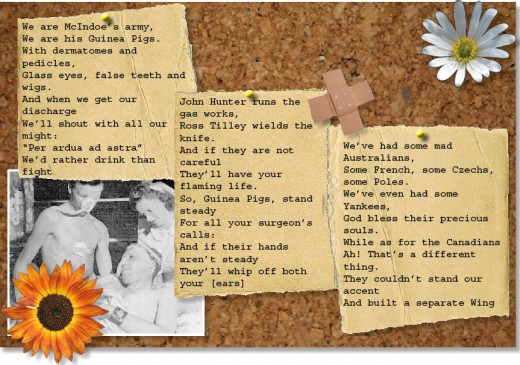

This very exclusive club was started in 1941 during WW2. There were exactly six hundred and forty nine members. But there was an incredibly high price to pay for membership.

Members were all airmen who had been badly burned and disfigured in action

They had all been treated by pioneer surgeon, Archibald McIndoe. He pioneered plastic surgery, hence the name of this elite club. Read on to learn more about this incredible and uplifting wartime story.

Archibald McIndoe believed that treating the physical injuries was just one side of his job. He taught the damaged men to live full lives and not to be ashamed of their terribly scarred faces and limbs.

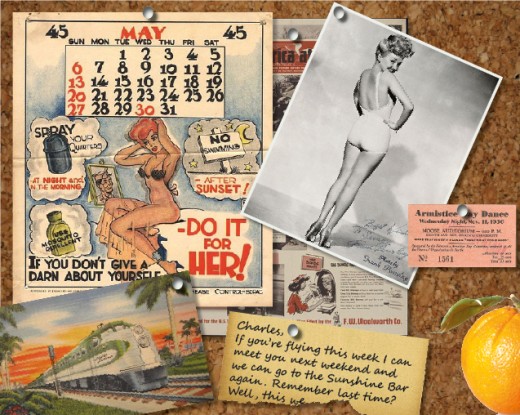

Airmen in WW2

Aircraft had first been used in war some years previously when the Royal Naval Air Service was formed in WW1. But by the nineteen forties much of the war was fought in the air. However, it was still comparatively new technology. The fuels that were used were not advanced and crashes often meant that even if an aircrew was not badly injured, flash fires often caused severe burns. The airmen’s faces and hands were exposed and vulnerable.

Archibald McIndoe resolved to help these men

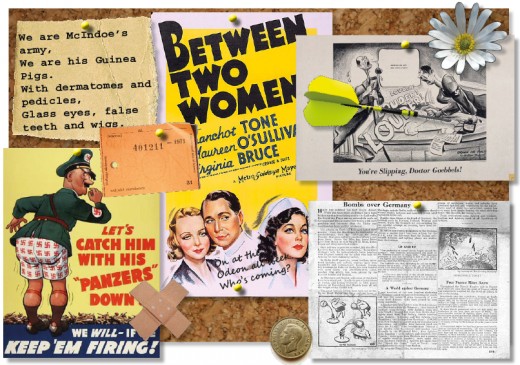

It seems strange to us today but then no-one really considered the problems that men with terribly scars would face when it came to trying to get back into society and their regular day-to-day lives. There was no counselling available and no after-care until McIndoe’s methodology.

Young men and teenagers

Few of the injured men had been in the forces before the war. They were just regular guys and most of them were very young. It’s easy to forget just how young they were. So many were still in their teens. They had received hasty training in how to fly, navigate or drop bombs but had no experience of war. They certainly had no experience of coping with horrific injuries.

Living a normal life

McIndoe set up his facility at East Grinstead. His revolutionary and experimental plastic surgery techniques rebuilt the men who he called ‘my boys’ but he didn’t act as though they were hospital patients.

He wanted them to live as normal a life as they could whilst they were in his care. Most of his boys were mobile most of the time and he encouraged them to wear normal clothes rather than hospital gowns. He also suggested that they wear their uniforms with pride. He created a barrack room atmosphere and there were always crates of beer available to help the men feel like ordinary men. He organised parties and sing-alongs around the piano – no doubt bawdy songs were the order of the day.

Some say that he chose his nursing staff well. He needed experienced and skilled nurses of course, but he also felt that attractive nurses were a morale booster for his boys. Hospital regulations at the time didn’t allow for personal relationships developing between nurses and patients but McIndoe paid no heed to this and there were several affairs and even marriages.

He included the local town in his rehabilitation process. He encouraged his boys to go into East Grinstead whenever they wanted to – for a drink at the local pub or to see a movie at the cinema. He didn’t want his men to be ashamed of their damaged faces; he wanted them to wear their scars with pride as they had been inflicted when the boys were serving their country.

The people of East Grinstead grew to know the men. Without pity or sympathy, they invited them to their homes for dinner or a drink. Local girls looked beyond the scars, appreciated the men behind them and were happy to go on dates or dancing with them. This wasn’t charity or sympathy – McIndoe made the townspeople realise that these boys were heroes and that it was the person that counted and not the scarred face.

The boys realised – thanks to McIndoe – that their lives weren’t over because of the way they looked. He, and the townspeople, were so successful in their work and acceptance that East Grinstead became known as:

And all the time, Archibald McIndoe was pioneering reconstructive surgery and rebuilding his boys’ faces and limbs. Six hundred and forty nine men were treated by him and entered the elite Guinea Pig Club. Because such surgery was a new field, they truly were ‘guinea pigs’.

The camaraderie he created was astonishing. For many years after the war,the Guinea Pig Club had regular reunions. Over the years their numbers have dwindled – we have to remember that anyone who was aged twenty one when the Second World War began would be coming up to one hundred years old today.

Archibald McIndoe died aged fifty nine in 1960. But his work continues to this day. Now his foundation is making a difference to the lives of burns victims – children, people who have been in house fires and accidents and, appropriately, those returning from the war zones of today.

.

.

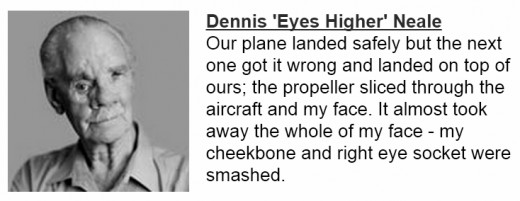

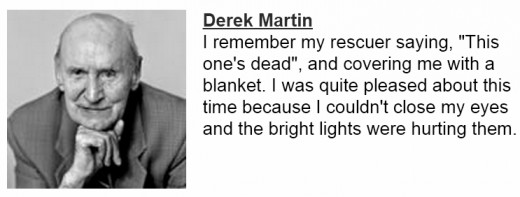

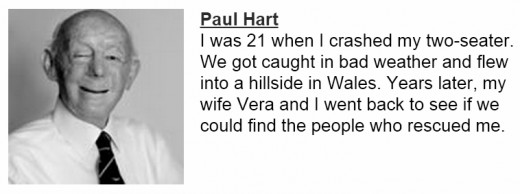

Meet some of the members of the Guinea Pig Club

See video:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR